Of Milk and Honey: Capturing the True Value of Apiculture

- Dave Black

- Oct 2, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Oct 3, 2025

Building on Ian Fletcher’s Revitalising Bee Science column last month imploring New Zealand’s apiculture industry to better promote its value to environment and economy, Dave Black casts his gaze wide – from the history of honey bees on these shores to modern global conventions which could provide the pathway beekeepers and scientists seek to advance bee research and support.

By Dave Black

From the very beginning New Zealand was sold to all-comers as a new pastoral paradise, a productive, benign landscape and – very literally given the preponderance of missionaries amongst its early residents – a biblical land of milk and honey. It wasn’t like that though. It’s ironic that neither cows nor honey bees had ever been seen in the country, but there was a united attempt to change that which had bees at its heart[i].

Early days

The earliest introductions of honey bees in the 1840s by Mary Bumby, William Charles Cotton, and Mary Allom were personal, but by the middle of the century the work of people like Charles Darwin and Gregor Mendel that unravelled pollination was being reinforced by practical experience.

The Rev. H. R. Peel, Hon. Secretary of the British Bee-keepers' Association, reported “The Rev. William Cotton introduced bees into New Zealand with the express object, of encouraging the growth of clover, which would not seed for want of its natural fertilisers... [the farmer] should have a warm corner in his heart for the bees because they fertilise the crops which feed his sheep and cattle.”

The next bee introductions were institutional, mainly by acclimatisation societies and pastoral groups who understood their relevance as economic and strategic benefits, not just for the colonists, but in a ‘factory’ for the Empire. By the 1870s bumble bees, or ‘humble bees’ as they were then, were in demand, mainly this time for red clover seed. Long-tongue bumble bees were eventually preferred for this purpose and in all there are eight bee species that were deliberately introduced for pollination[ii] between 1839 and the 1970s.

In those British pioneering days, pollination and increasing biodiversity was a central theme in the economic development of New Zealand. By 1886 The Australasian Bee Manual produced by Isaac Hopkins was very clear about the value of bees to agriculture, with one chapter (third edition, Ch.XIX, pp297-307) used to discuss it. A footnote explains an attempt to sue a beekeeper for damages (a US farmer’s sheep were having ‘their’ nectar stolen by the bees) had thankfully been dismissed as absurd by the courts, but the case certainly made a stir in beekeeping circles everywhere.

Shall we mention money?

In recent years several attempts have been made to quantify the financial value of pollination, particularly that of honey bees. For New Zealand a crude estimate has been reported using data from 1992[iii]. It simply added the total value of fruit crop and vegetable seed production, and further added a figure for the pollination of pasture legumes. $1.005 billion + $0.211 billion + $1.872 billion = 3.088 billion.

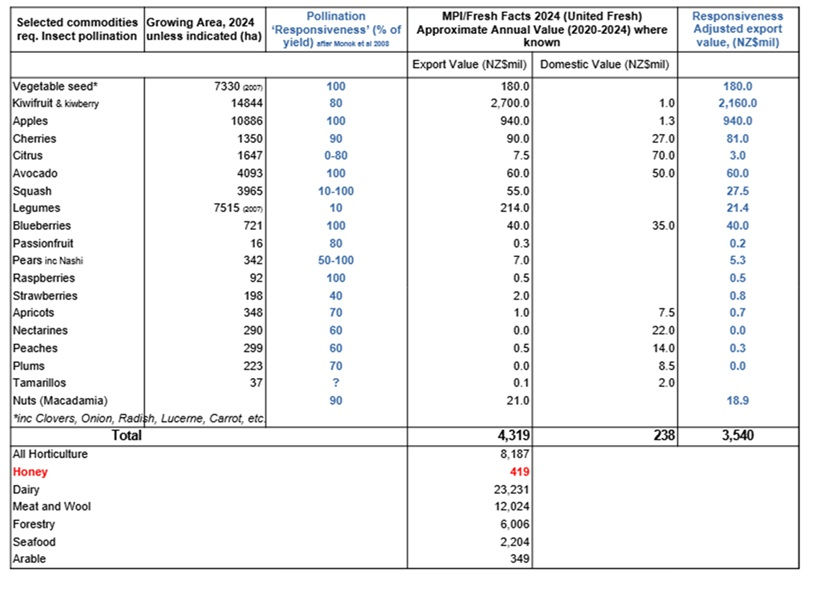

It’s a figure that has passed into folklore, but while it’s wrong and the calculations have been refined since, the estimate hasn’t been reassessed as far as I can tell. It remains a difficult thing to do[iv], but just to set the figure in a more up-to-date context (also imperfect!) the accompanying table sets out more recent figures for New Zealand.

The current value for honey exported is $419 million (maybe another $2-3m for wax, package bees etc)[v] which compares to the value for all entomophilous pollination (not just managed bees), at say, $3.54 billion. It’s also worth remembering that the $419 million comes from honey sold at an average of $40/kg, a figure highly skewed by mānuka pricing. Globally, export honey generally is traded at $10/kg or less.

Even a more rigorous calculation isn’t likely to change the proportions; the financial value of pollination to the country dwarfs the value of honey, whatever the price per kilo. As it is, it represents about half the value of all of the country’s horticultural exports, and compares to a total export revenue for all New Zealand’s primary industries of a little more than $58 billion[vi].

Who cares about the future?

While it might have escaped your attention, New Zealand is one of 196 countries that are members of the Convention on Biological Diversity, and has been since 1993. By the time of the UN’s Earth Summit in 1992 the world had recognised that biological resources (like pollinators) are what fuels humanity's economic and social development right now and into the future, and therefore that “the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits” needed to be managed somehow at a global scale.

In the face of human activity already responsible for an alarming rate of species extinction, thus limiting use of plants’ natural resources, the Convention began to form the mechanism for sorting that out. By 2002 – backed by mounting academic and wildlife institution research proving the importance of bees as a lynchpin species in ecosystems and to the pollination networks that underpin human food security – the global Convention met in Sao Paulo. Emerging was a ‘Declaration’, the International Pollinators Initiative (IPI), a measure which would try to ensure the conservation and sustainable use of pollinators in agricultural ecosystems.

The IPI’s major role is to “promote coordinated and proposed action worldwide” and it is the global policy platform for pollinators, including bees[vii]. The Sao Paulo workshop identified the risk of depending on a single pollinator species (honey bees, which didn’t appear to be doing all that well), while the opportunity to use alternatives was rapidly being closed down as land-use and management practice spoilt the environments they lived in.

A local context

Many countries have taken up the call and produced strategic, national plans to support pollinators and the ecosystems we share, formed by the principles set out in these agreements.

New Zealand has a biodiversity strategy published in 2020, Te Mana o te Taiao Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy, which robustly acknowledges that “People are part of nature and nature supports life and human activity. All aspects of our wellbeing, physical, cultural, social and economic, are dependent on nature and the services that it provides. Natural wellbeing underpins our lives, lifestyles and livelihoods. Nature is valuable for its own sake... and is linked to our identity as New Zealanders.”[viii]

That’s all largely performative. What it hasn’t done, in any obvious way, is to integrate the Sao Paulo pollinators IPI declaration into its biodiversity strategy. France has, Spain has, Norway has; the United Kingdom, Netherlands, Australia and Ireland have, and there will be plenty of others in languages I can’t use.

The IPI should be the natural territory of the apiculture community in New Zealand. As a rule, what’s good for natural ecosystems is good for honey bees too.

Te Mana o te Taiao does introduce a concept of a ‘valued introduced species’, something surely that covers our introduced bees. The policy defines valued introduced species as “...sports fish, game animals and species introduced for biocontrol, which provide recreational, economic, environmental or cultural benefits to society... [we will] recognise and prioritise the special responsibility we have towards indigenous species, while still recognising the recreational, economic and cultural benefits and human sustenance [provided by] valued introduced species.” Hardly a pollinator policy, but it’s a start.

Where does apiculture fit in?

The strategy has no mention of honey bees; no apicultural organisation is mentioned with a role in New Zealand’s biodiversity management, no producers, no statutory body, there are no targets that relate to bees of any kind, or their keepers, and the only legislation apparently relevant is the Biosecurity Act, and that’s not really about bees, but pathogens of bees. The word ‘pollination’ appears once. Nothing informs the thorny problem of beekeepers using DOC land for example.

Two local organisations contribute to pollinator support, Trees for Bees, and Syngenta (Operation Pollinator™, with the Bioeconomy Science Institute) and these are not initiatives derived from Te Mana o te Taiao.

As a nation, a natural lack of diversify of pollinators starts us off on the back foot, and we knew it 150 years ago. It makes food production particularly vulnerable to degraded ecosystems and climate change,[ix] as simultaneously the proportion of crops that require or benefit from insect pollination have increased.

According to a Parliamentary briefing presented in 2023, world-wide consumers are expected to need 56% more food by 2050. The briefing foresees a significant demographic shift to Asia and Africa, more localisation of food supply, and the rise of food sovereignty[x].

Increasing too is the amount of pollination that needs to be managed, partly because wild pollinators have diminished, but also because the supply-chain demands it; proper pollination improves the nutritional and aesthetic quality, storage, and timeliness of crops to market. That too is food security. It cannot be left to chance.

Making the most of it

The way to make apiculture more economically relevant than it is should be by prioritising support for its most important activity, and then accommodating the production of ancillary goods, honey, wax, etc. The trouble has been that the most important function produces somewhat intangible benefits which invisibly accrue to several beneficiaries, so it’s not adequately rewarded. It’s hard to attach a financial value, but the IPI provides an opportunity to develop a more valuable collective purpose for apiculture than just an insular, and minor, commercial lobbyist for honey[xi]. It’s also a way to set the rules of the game.

Besides moulding policy and creating strategic connections with sympathetic bodies we should be positioning the apiculture sector as experts at using beneficial insects to sustain our food quality and security, making it part of our culture, and part of our businesses. Apiculture already inspires relevant research within the academic community and manages an insect model that provides insights for many aspects of the life sciences, and applications as diverse as computing, aeronautics, gerontology, and the defence industry.

What bees actually provide is skilled labour, an ability to learn, their own transport, and an unmatched efficiency at transforming energy into work. Beekeepers – apiarists – have expertise that could be turned to supplying or brokering other pollinators for orchards, tunnels, and glasshouses; they could be managing supplementary or complimentary means of pollination; offering specialist crop consultations or field assessments, perhaps providing biological pest controls, habitat management, and environmental monitoring, supported by companies that provision an invigorated apiculture.

That probably requires support for beekeepers to structure their business relationships differently. It’s not only about honey bees, but about imaginatively developing a future. I think we all need to lift our gaze.

Dave Black is a commercial-beekeeper-turned-hobbyist, plus harvest, inventory, and pollen mill manager for Seeka Ltd in the kiwifruit industry for 20 years, now retired. He regularly contributes to Apiarist’s Advocate as a science writer.

References

[i]For more and an interesting perspective see; Parker, H.E., 2022. Honey and Humble: Bee Introductions, Environment, and Ideology in Aotearoa New Zealand, 1839-1900 (MA (History)). Waikato.

[ii]Apis mellifera (L.), the bumble bees: Bombus terrestris (L.), B. subterraneus (L.), B. ruderatus (F.) and B. Hortorum (L.); the lucerne leafcutting bee: Megachile rotundata (F.); the alkali bee: Nomia melanderi (Cockerell) and the red clover mason bee Osmia coerulescens (L.). Howlett, B.G., Donovan, B.J., 2010. A review of New Zealand’s deliberately introduced bee fauna: current status and potential impacts. New Zealand Entomologist 33, 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00779962.2010.9722196

[iii]Gibbs, D., Muirhead, I.F., 1998. The Economic Value and Environmental Impact of the Australian Beekeeping Industry, A report prepared for the Australian beekeeping industry

[iv] See, for example:

Gill, R.A., 1991. The value of honey bee pollination to society. Acta Hortic. 62–68. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1991.288.4

Gibbs, D., Muirhead, I.F., 1998. The Economic Value and Environmental Impact of the Australian Beekeeping Industry, A report prepared for the Australian beekeeping industry.

Rucker, R.R., Thurman, W.N., 2001. An Empirical Analysis of Honeybee Pollination Markets.

Gordon, J., Davis, L., 2003. Valuing honeybee pollination: a report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. Rural Industries Research & Development Corp., Barton, A.C.T.

Monck, M., Gordon, J., Hanslow, K., 2008. Analysis of the market for pollination services in Australia. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, Barton, A.C.T.

Keogh, R.C., Robinson, A.P., Mullins, I.J., 2010. Raising the Profile of an Undervalued Service

[v]MPI Apiculture Monitoring series/MAF Conference reporting 2002-2024

[vi] Situation and Outlook for Primary Industries (SOPI), MPI Economic Intelligence Unit, June 2025. ISBN No. 978-1-991380-01-2 (print) ISBN No. 978-1-991380-02-9 (online)

[vii]Dias, B.S.F., Raw, A., Imperatri-Fonseca, V.L., 1999. International Pollinators Initiative: The São Paulo Declaration on Pollinators.

[viii]Te mana o te taiao: Aotearoa New Zealand biodiversity strategy 2020. Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand

[ix]See: Howlett, B., Butler, R., Nelson, W., Donovan, B., 2013. Impact of climate change on crop pollinator in New Zealand. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.8051629

Newstrom-Lloyd LE 2013. Pollination in New Zealand. In Dymond JR ed. Ecosystem services in New Zealand – conditions and trends. Manaaki Whenua Press, Lincoln, New Zealand

Pattemore, D., 2013. Recent advances in pollination biology in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Botany 51, 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.2013.813558

Howlett, B.G., Evans, L.J., Kendall, L.K., Rader, R., McBrydie, H.M., Read, S.F.J., Cutting, B.T., Robson, A., Pattemore, D.E., Willcox, B.K., 2018. Surveying insect flower visitors to crops in New Zealand and Australia https://doi.org/10.1101/373126

[x]The Future of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Food Sector Exploring Global Demand Opportunities in the Year 2050. A Long-term Insights Briefing presented to the House of Representatives pursuant to section 8, schedule 6 of the Public Service Act 2020, Ministry of Primary Industries, ISBN No: 978-1-991080-23-3 (online), ISBN No: 978-1-991080-24-0 (print)

[xi]New Zealand Honey Strategy 2024-2030. Thriving Together, Futureproofing New Zealand Apiculture, Apiculture New Zealand. https://apinz.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/NZ-Honey-Strategy-2024-2030-FINAL-version-for-web-20-Feb.pdf

Comments